The ghost told Sanderson that she needed more information. So she’s off to get more information from Decatur County’s unofficial historian, Miss Angela Farr. But will more information solve Sanderson’s problems, or raise new ones? Find out in chapter 9 of Nightfeather: Ghosts, “In which Miss Angela Farr reveals the history of the Maverick Mine.”

The chronology of this chapter is based in facts about silver mining and the use of silver as currency in this country. While it has has taken a back seat to gold in popular imagination, silver has a long history as a treasure metal. In various eras, some countries have based their currency on silver in preference to gold. Indeed, China’s demand for silver in the nineteenth century is sometimes held responsible for the chain of events that set off the Panic of 1837 here in the United States.

That’s because the United States was on a bimetallic standard in those days. The dollar was pegged to gold and silver. And the Mint produced coins that had just about their face value in one of those two precious metals. It had been that way since 1792.

One of the ideas behind bimetallism is that it gives your national currency flexibility: money can be coined in gold or silver or both, and the Mint usually tried to produce both. The problem is that for bimetallism to work, you have to set a fixed ratio for the value of the two metals, and in the real world, the ratio fluctuates. The United States had set the ratio to 15 to 1 way back in 1792. One ounce of gold was worth just about $20, but it took 15 times that, or 15 ounces of silver, to be worth $20. Got it? The problem was that the price of silver relative to gold on the open market kept dropping. So, for example, the silver in five silver dollars was worth less on the open market than the gold in a five dollar gold piece. If you wanted to make a quick profit, you went to the Mint with five silver dollars, exchanged it for one five dollar gold piece, melted that down, and sold it for more than five dollars in silver on the open market. The Mint couldn’t keep gold coins in circulation, they were melted down so fast.

Thanks to the financial problems caused by the Civil War (1861 – 1865) and the adoption of the gold standard by many European countries, the United States decided to adopt a gold standard in 1873. But the silver miners protested! If they couldn’t get the Mint to accept their silver at the old 15-to-1 ratio, the price of silver would drop even more. But support for the gold standard was strong on Wall Street. It took the silver interests five years to get the Mint to agree to a limited program of buying silver at the old price. It helped, but not much. The silver mining companies kept complaining.

And then at the end of the 1880s, another political movement entered the scene. It was made up of farmers in the South and Plains states. They were being pinched by a drought on the Plains and the tight money policy caused by the gold standard. They wanted an increased issue of paper money, but they were willing to make common cause with the silver interests, and managed to get the Sherman Act passed in 1890, greatly increasing the amount of silver the Mint was required to buy and coin.

Unfortunately for the silver interests and the farmers, there was a financial panic in 1893. One of the features of the Sherman Act was that people could exchange silver for gold and make a profit, just as they had in the old days of bimetallism. In the aftermath of the panic, the Treasury saw its gold reserves being rapidly depleted. So the Sherman Act was repealed.

The silver mining interests, which included the mine owners, the miners, and the states that collected taxes from them, all raised a howl. They got together with the farmers, who were now organized into the People’s Party, or Populists, to push for what they called “the unlimited coinage of gold and silver.” The silver interests saw that as a way to raise the value of silver. The farmers saw it as a way to get cheap money and pay off their debts.

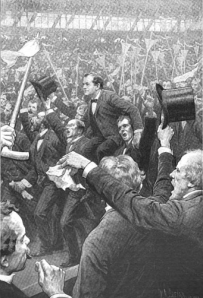

In 1896, they managed to capture control of the Democratic Party, and nominate William Jennings Bryan, who espoused their cause in his famous “Cross of Gold” convention speech. Hopes rode high, only to be dashed in November when the “gold bug” candidate of the Republicans, William McKinley, won the election. That was the last stand for the silver interests. The gold bugs in Congress went ahead and passed a law definitely decoupling the dollar from silver and making the gold standard the only monetary standard in 1900. And the silver interests never recovered. Neither did the farmers; the People’s Party disintegrated after 1896.

“…went ahead AND passed a law…”

Great background — interesting to contemplate in light of modern-day gold bugs!

Mental note to self: must always check text all the way to the end, as I’m less likely to have reviewed it often. Thank you for the correction!

More broadly, the conflict between the silverites and Populists on one hand, and the gold bugs and Wall Street on the other, is an early version of the continuing debate about which of the Federal Reserve’s two missions it should give priority to: price stability or full employment.

Your posts are always bulging with information, yet succinct in delivery. I keep trying to emulate; one day I’ll succeed – the day I learn to curb my verbosity.

Loquaciousness, CP, loquaciousness. It sounds better. And if you didn’t have it, you’d not be writing stories in the first place.

I suspect that part of my writing style for these historical posts comes from a job I took on a few years ago, writing encyclopedia entries!

Wow, yeah. But I thought it was scriptorrhea. And I too have experience of the clipped style – try press releases and advertising copy, going out on air at £x/sec! Maybe it’s in rebellion of that.

I can see the rebellion angle. I have so gotten after my students for their writing style that I have tended to the opposite extreme.

There was a recent humor piece that captured exactly what’s wrong with the writing style of college students, that you might find entertaining: http://www.collegehumor.com/article/6941975/if-everyone-still-wrote-like-they-did-in-college

Ok, had to haul myself back; I don’t often ‘surf’ but curiosity got me. Do kids really dress up like for the proms? Not in UK they don’t.

Kids still do dress up for proms. Though I have none of my own, I’ve seen enough in my Facebook feed in the last few years to know it’s an ongoing tradition. And by and large my friends are living in the northern part of the country, where such things are less extravagant.

I just thought about it now, a week or so after reading this post. You may find it interesting to know that in Hebrew the same word (“kessef” – really easy to pronounce, isn’t it? :)) is used for both “money” and “silver”. When you say in Hebrew “I have no money”, it also means “I have no silver.” On the other hand, the allowances kids receive from grandparents in Hanukkah, (at least in my family) were called in Yiddish “Hanukkah Geld”, “Hannukah Money” – and I assume “Geld” here came from an old German word for gold.

So Judaism is a bimetallic faith. 🙂

I’d known about the Hanukkah Geld, but I didn’t know about the silver=money identity in Hebrew. Thanks for the information!